A 2017 survey by Central Bank of Jordan (CBJ) and GIZ found that informal finance – a challenge in the face of resilient, inclusive development – is quite unevenly affecting a large part of the population. Responsible digital financial inclusion is now on the agenda and providers face a significant market potential.

Informal financial services cover privately held savings or loans by private lenders as well as semi-formal services provided by companies and are not specifically authorized by the financial regulator.

What does data tell us?

The use of informal financial services is especially high when it comes to credit. More people, aged 15 and above, took a loan from an informal source (13.3%) than from a formal source (9.9%) such as a bank or microfinance institution in 2017. Among the informal lending sources, family and friends were the most popular (11.3%), followed by an employer (1.9%), or another type of informal lender (0.6%). People do not borrow (aside from not needing a loan) due to religious beliefs, high costs, too much debt, strict collateral requirements, or excessive documentation requirements.

Although formal accounts are more popular, informal savings are significant. Around 13.1% of people held informal savings, compared to about one third of respondents (33.1%) having an account, either with a bank (32.0%), postal savings (1.1%), or mobile money provider (0.9%). The mechanisms for informal savings need to be better understood, yet they likely represent a combination of informal savings groups and semi-formal arrangements by associations and cooperatives. People do not have formal accounts, reportedly, because they do not think they need one, due to high fees or minimum balance requirements, again religious reasons, or difficult opening procedures.

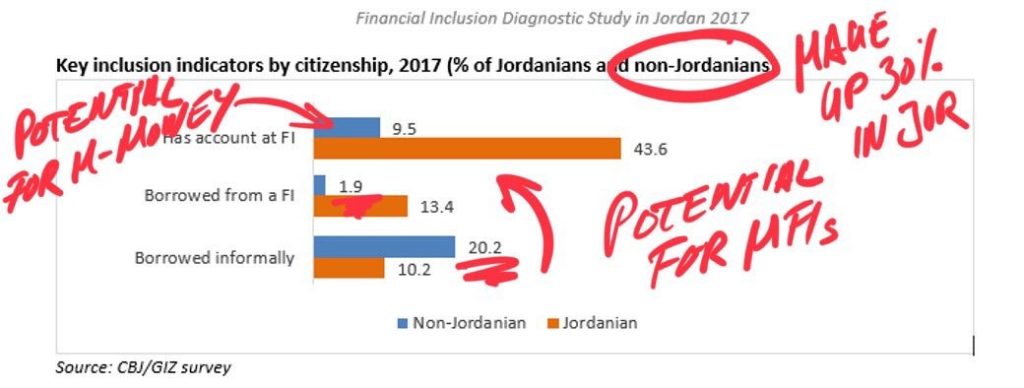

Particularly astounding is the discrepancy in the usage of informal finance versus formal finance among Jordanians and non-Jordanians, i.e. around 2.9 million people residing in Jordan, mostly migrant workers and refugees. Non-Jordanians borrow around twice as much informally. They have around four times less a formal account. These figures distort aggregate access and usage rates (again, non-Jordanians make up around a third of the population). In any case, they indicate a real market potential for financial service providers in this segment.

Easy cash, bad habit

Informal finance may be attractive to people due to quick, uncomplicated availability of money at seemingly favorable terms, especially during shocks. Borrowing among friends and family, for example, may be interest-free and have indefinite repayment periods. However, borrowers may face difficulties in the absence of any regulated protection or collection schemes. In the case of using private money lenders, microcredit borrowers may be exposed to hidden charges, unclear terms, and aggressive collection practises. Such practise has already triggered crises in other countries.

Digital financial transformation

A shift from informal finance to formal finance could better protect the financially marginalized or vulnerable segments of the population, usually the first ones to use informal loans, and improve the overall stability of the financial system. Such a shift, however, requires change on the policy, regulatory, infrastructure and provider level to make formal financial services more conveniently accessible and in emerging markets today this is mostly driven by digital financial ecosystems and services. In any event, empowering and incentivizing people and businesses to enter the formal sector entails a mix of actions. In Jordan, recently taken bold moves boil down mainly to:

- First, the financial regulator in collaboration with payment service providers (issuers of e-money) is creating a widely accessible, user-friendly ecosystem for mobile accounts as simple alternatives to bank accounts. Mobile wallets are being linked to payment cards. Utility bills can be paid on the go. Government agencies are switching to the digital transfer of benefits and salaries into mobile accounts. Humanitarian agencies have done so for cash assistance.

- Second, MFIs, since 2018 fully licensed, including new Islamic finance providers, have been reaching out to an ever increasing number of women and low-income segments. Microfinance and DFS markets are converging as MFIs act as mobile money agents and start to disburse and collect loans digitally. A credit bureau which collects data on borrowers from banks and more and more MFIs ensures that they do not get unnecessarily served again by others.

- Third, the CBJ has brushed up the consumer protection framework in an effort to make fair treatment, price transparency, and ways to complain common practise across service providers. The King Al Hussein Fund together with the Ministry of Education has introduced financial education programs in schools.

Under Jordan’s Financial Inclusion Strategy 2018-20, the authorities and private sector are actively embracing the potential of responsible financial inclusion of people and businesses in a coordinated manner. GIZ has been a partner of the CBJ and other authorities in most of these domains concerning financial inclusion policy, DFS, and microfinance sector reform since 2012.

By Atilla Kaiser-Yuecel, Artur Vacarciuc